I love podcasts. I listen to them while I'm working, while I'm cooking, while I'm cleaning, while I'm doing art, whatever-- if I could listen to them in my sleep, I would. The TED Radio Hour isn't necessarily my favorite one, but I listen to it from time to time, and the March 6th show looked especially interesting: math! Real-life applications! Fun! It probably wouldn't teach me anything I didn't already know, but it would be an appropriate way to to pass the time while peeling apples for my Super Pi Day pies. So I loaded it up and started listening.

A lot of the material was familiar to me, including most of Hannah Fry's segment on the mathematics of love and dating. I've heard a lot about OKCupid's data analysis, and I'd read about that experiment where the couples discuss a contentious issue and scientists use their conversation to predict whether they'll divorce. I'm also well-versed in the secretary problem-- though I had never thought to use it the way Fry was using it.

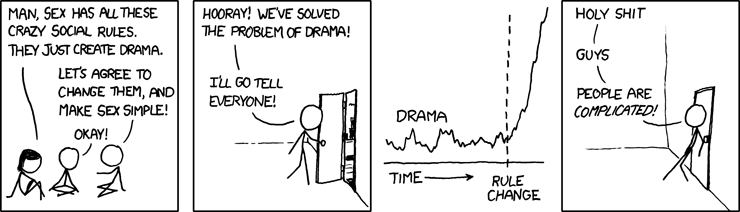

|

| No, not that one. |

Which is why it's probably pertinent to explain that in its earliest incarnations, the problem was called the "Marriage Problem," not the secretary problem. The scenario makes more sense in this context: In your lifetime, you're going to date a given number of people. You have to date them in succession, and at some point in each relationship, you gotta decide whether to marry this person or break up. Once you've broken up with somebody, you can't get them back. And once you marry somebody, you don't get to keep looking for more candidates. Given these parameters, how do you maximize your chances of marrying the right person?

The secretary/marriage problem does have a solution, but it's not a terribly romantic one: reject the first 1/e percent of the applicants (about 37%), and make sure to rank them all relative to one another. Then, as soon as you come across someone you like better than you liked the best-ranked of the rejects, accept that person. It's not a foolproof method, but you're unlikely to end up with a bad match by following it.

Fry and the host of the podcast discussed using the optimal stopping solution to the marriage problem in one's own love life, and admitted that it presents practical problems. The host was dismayed that more than a third of the time, you'll reject someone just because they showed up too soon, even if you're perfect for each other.

I would never set out to use the optimal stopping solution in my own life. It's an oversimplification of a complex, human problem with a billion different factors, and it's not just my own heartbreak on the line. I can't imagine breaking up with somebody by telling them "it's not you, it's 1/e."

That being said...

Just for kicks, I used the formula from the podcast to estimate the number of people I'm likely to date in my lifetime. I've been dating for 10 years, and I've dated 6 people (three long-term relationships, three casual-date situations), for a rate of a new suitor roughly every one and a half years. I'm not a very energetic dater.

Let's say I plan to continue dating at this rate until roughly age 40: by then, I'll expect to have found my match and settled down, or abandoned the search to devote my life to other pursuits. That gives me approximately 15 suitors over the course of my life. Sounds a little on the high side, but not outside the realm of possibility. I've already met, dated, and ultimately rejected 6 of my potential 15, so that means...

...I've rejected the first 1/e percent of my n suitors. I've somehow fallen ass-backward into an optimal stopping solution.

It's not what I intended, but I suppose as long as I've already completed the first half of the problem, I might as well carry through with the second. It would be difficult to rank those six fellas with respect to one another, but I have a clear idea of who was best and who was worst. Let's call the best one Jean-Luc, and the worst one Wesley.

If you've ever heard me tell a funny story about an ex, there's like a 5000% chance it was about Wesley. He's the one who tried to use Count Rugen's pain-machine speech from Princess Bride as sexy dirty talk. He's the one who cheated on me with anyone who held still long enough. He's the one who believed that his emotions controlled the weather. He's the one who-- I swear I'm not making this up-- said he was an astral being from a higher plane of existence, cursed to walk the earth in a mortal body as punishment for some kind of hubris-related sin. Yeah, I don't know what I was thinking, either.

|

| I spent most of this movie warning Jane to run away because honey, trust me: you want none of that. |

I initiated the breakup. It was the right decision, but that didn't make any of it feel good. He didn't do anything wrong. He deserved somebody who loved him more than I loved him: somebody who would give him a carefully considered 'yes' or 'no' when asked to travel the world with him, not laugh in his face. I don't regret ending any of my relationships, but that's the one that still keeps me up at night sometimes--knowing I did the right thing, but wishing there were some other, better, less painful thing I could have done.

|

| "I can never regret. I can feel sorrow, but it's not the same thing." #lastunicornfeelings |

To maximize my chances of marital bliss, I need to judge each of my future relationships against the relationship I had with Jean-Luc. If they don't measure up, I reject them and move on; but the first one who surpasses Jean-Luc is the one to whom I propose. (And yes, I'm pretty sure that if I get married, I'm going to be the one doing the proposing-- I've been the instigator in each one of my romantic endeavors, I don't see that changing.)

The math used to derive the optimal stopping solution is a little beyond me, so I can't work out my precise probability of success. Instead, I set up a list of my 15 suitors, assigning ranks to the 6 past suitors and 9 future ones according to their desirability. I duplicated and randomized the list 30 times in such a way that the past and future dudes would be shuffled together, but the relative desirability of each group would remain the same-- any number of mystery future dudes could be ranked more desirable than Jean-Luc, or less desirable than Wesley, but Wesley would always be ranked less desirable than Jean-Luc. Then, for each of the 30 shuffled rankings, I randomized the order in which I would meet the nine future suitors, and took note of what the outcome would be if I followed the advice of the secretary problem.

In 7 out of 30 cases, the overall most desirable candidate for marriage was among the future suitors, and I met him before I met anybody else surpassing Jean-Luc. We married, and lived happily ever after.

6 times out of the 30, there were multiple future suitors who ranked better than Jean-Luc, and I didn't meet the best of them first. In those 6 cases, I married the second-best overall candidate, and stopped dating. As far as I knew, I'd married the best guy. Still a pretty happy ending.

Finally, 17 times out of 30, no future suitors ranked better than Jean-Luc. In these cases, I proposed to no one, and presumably died surrounded by cats.

|

| I REGRET NOTHING |

A lot of the traditional reasons people get married don't apply to me. I don't want to have children, so I don't need a father for them. I support myself financially, so I don't need a breadwinner. My friends and family provide really great companionship, and I wouldn't describe myself as lonely. As for that other big reason people tend to pair off with one another, well... modern technology works wonders for the single gal, is all I'm saying.

If I was set on finding a good spouse no matter what, this calculation would be extremely disheartening. Still, the calculations provided some startling clarity, if not a perfect set of instructions for happiness. There's still good advice to take away from this.

In the past, I've worried over the question of whether my romantic partner made me as happy as I could possibly be, or if I'd be happier with somebody else, but then if I break up with him what if he was The One, but if I stay what if I'm miserable, etc, etc. Optimal stopping says that's not the way to think about it. The main question I should ask myself, upon entering into a new romance, is: Am I happier with this person than I have been when I was with anybody else, and am I happier with them than I am when I'm single?

If the answer is yes, then that's good enough. And if it's no, then that's good enough, too.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment