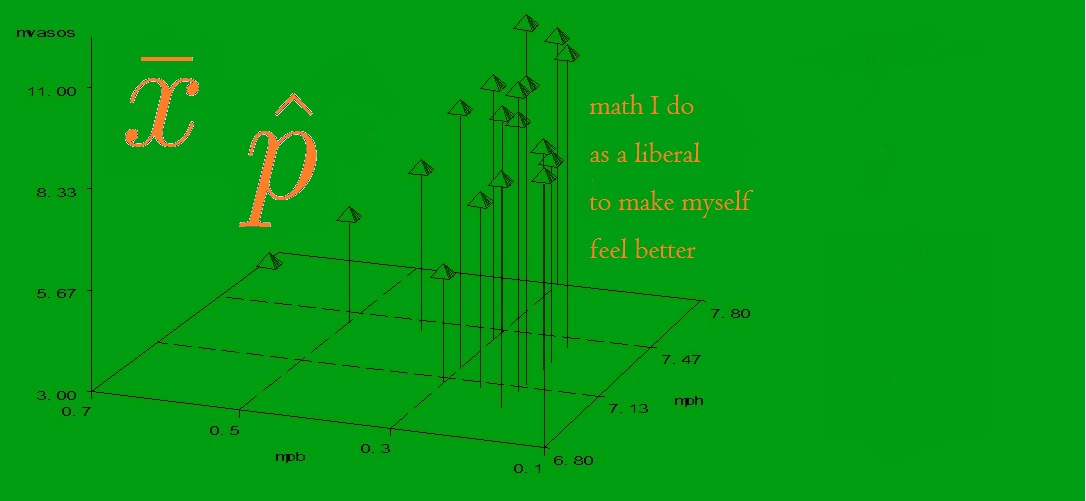

Here's some graphs of the data from four different stations who've completed surveys in the last few weeks. In these graphs, each dot represents a particular song, "familiarity" represents the proportion of respondents familiar with the song, and "contempt" represents the proportion of those familiar who said they were sick of hearing it.

I've also included the regression formula, R-squared, and R values on each of these graphs. See, in a linear regression formula, the number in front of the x is the important one: it tells us whether the correlation is positive or negative. The R value tells us how strong the correlation is: when R is close to 0, the relationship is weak; when R is closer to +1 or -1, the relationship is strong. (To be technical, the R value tells you the proportion of the variation in your data that can be explained by the linear relationship rather than random error. The more variation you can explain, the better your model!) The y-intercept is important for positioning the line, but otherwise useless for analysis. It's just telling you the projected contemptibility of a theoretical song with 0% familiarity, which doesn't mean anything. Don't take y-intercepts too seriously in regression analysis. They're just out to confuse you.